- Cash-strapped governments throughout Pennsylvania are getting concrete help with their problems from Carnegie Mellon University

Anyone who has lived in Pittsburgh knows that a better name for late winter might be "pothole season," as craters big enough to swallow a Smart car or two rip open the city's roadways.

But it was a bump in the road--quite literally--that Takeo Kanade didn't expect when he first came to Carnegie Mellon three decades ago from the milder climes of Japan. The problem has continued to vex Kanade over the years, his frustration intensifying with each new pothole encounter.

"One day I was driving down Fifth Avenue, and there was a huge pothole I didn't expect and couldn't avoid," says Kanade, the U.A. and Helen Whitaker University professor of robotics and computer science at CMU. "Those are very bad experiences."

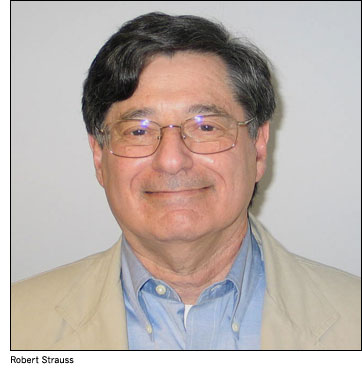

Pittsburgh motorists are all-too-familiar with these "very bad experiences," but with perpetually tight city finances, overworked road crews can't always keep up with repairs or even locate all the potholes in order to fix them. That's why Kanade recently set out to use his computer vision expertise to help develop a system--called the Road Damage Assessment System, or RODAS--to detect and report potholes.

When people think about universities helping local governments and public agencies, state-run schools and land-grant colleges often come to mind--not private institutions like Carnegie Mellon. But a number of projects such as RODAS are under way at the university--many from the School of Computer Science--to help cash-strapped municipalities meet the challenges they face in an era of shrinking budgets.

It's a trend rooted in Carnegie Mellon's historical emphasis on tackling real-world problems, says Jennifer Meccariello Layman, CMU's assistant director of government relations, and it has its roots both in Andrew Carnegie's drive "to do real and permanent good in the world" and in the work of the original Mellon Institute of Industrial Research.

"Even though Carnegie Mellon has evolved into a really elite institution, the faculty and students and staff look at Pittsburgh and western Pennsylvania as this wonderful test bed for their research," Layman says. "You can build all the computer models you want and write all the algorithms you want, but if your technology doesn't work when you go out into the real world, what's the point?"

It doesn't get much more real than being stranded in sub-zero temperatures after blowing out a tire on a nasty pothole.

RODAS allows anyone to upload a photo of a pothole and then pinpoints the image on an online map, creating a public repository of road conditions. It was developed together with Robert Strauss, professor of economics and public policy in CMU's Heinz College, and former graduate students Todd Eichel and Veronica Acha-Alvarez.

Last winter, more than 600 potholes were reported across Pittsburgh using RODAS. And there is interest from the Pennsylvania Association of Boroughs in deploying the system in some of the 958 municipalities the organization represents statewide. "We have to protect the investment we've made in our public infrastructure, and most local governments don't have the resources to invest in a solution like this," says E.J. Knittel, the association's director of events and information services.

Other SCS technologies are also putting the power to improve community services right in the hands of the community itself. This past summer, researchers at the Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Accessible Public Transportation, or RERC-APT, a collaboration between CMU and the University at Buffalo, released a free mobile crowd-sourcing app that allows Port Authority of Allegheny County riders to signal the location and occupancy levels of their buses.

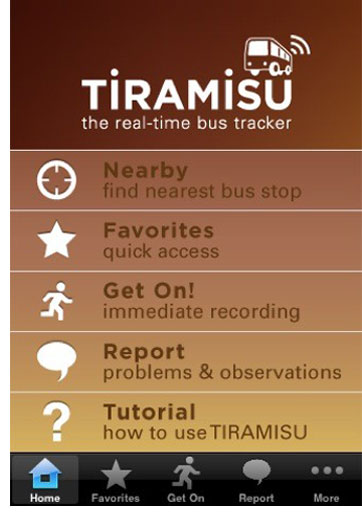

Called Tiramisu--Italian for "pick me up"--the system counts on people to activate the application on their smart phone when they get on the bus, record how full the vehicle is, and press a button allowing the phone to share a GPS trace with a server that relays the information to other riders at later stops.

In this way, transit users can get real-time reports about whether their bus will arrive on time and find out if there will be space on board--information of special concern to riders with disabilities, according to Robotics Institute senior systems scientist Aaron Steinfeld, co-director of RERC-APT, who leads the Tiramisu team with SCS colleagues Anthony Tomasic and John Zimmerman.

"Where's the bus? Am I going to get to sit down?--these are questions everybody asks, but it is really valuable information if you need space for a wheelchair or it takes you extra time to reach your stop," Steinfeld says.

While most Port Authority buses have a GPS box used to notify riders about upcoming stops, these units aren't connected to a backend server that would be needed to remotely monitor bus location. To engineer its own real-time tracking system would cost the Port Authority millions of dollars it doesn't have; the agency's projected $64 million budget deficit for the coming fiscal year could yet lead to deep service cuts.

"Real-time information is something that's been in demand, but unfortunately, it's something we can't afford to offer," Port Authority spokeswoman Heather Pharo says. "We're extremely fortunate to have an institution like Carnegie Mellon that looks at problems and recognizes our limitations and then comes up with an ingenious workaround solution."

More than 18,000 recordings were made in the first few months after the release of Tiramisu in July, and the value of the app (available for iPhone and Android platforms) will grow in proportion to the number of users. If no one is using Tiramisu on a particular bus, the system predicts arrival times using historical data or the bus schedule.

"What we really hope is that it becomes self-sustaining in terms of the data being generated," Steinfeld says. "But we don't know yet what the critical mass is for the system. It's one of the very interesting research questions that Tiramisu lets us explore."

Plans are also in the works to study the motivations that compel riders to help each other by using Tiramisu and to explore whether the system could be of commercial value in other locales.

"Pittsburgh is very much a city where people want to help each other, so we are a little nervous about going to other cities," Steinfeld says. "But we are hoping this desire to want to help your fellow rider is something that transcends location."

Tiramisu, Pharo says, has improved the transit experience for Port Authority customers and has the potential to boost ridership--outcomes that make the hard work both fun and worthwhile to the researchers.

"Any research that you do that is out there in the real world is more enjoyable than research that is hidden away in the lab," Steinfeld says. "And this is the best kind of research. It's not just research in the wild--it's is actually being used in the wild."

Data from Tiramisu are being put to even further use to help power Let's Go, a spoken dialogue system developed by CMU Language Technologies Institute principal systems scientist Maxine Eskenazi and her colleagues that provides automated schedule and route information to Port Authority riders.

The Port Authority operates bus, light rail, incline and para-transit services for nearly 230,000 daily riders. The agency customarily staffed its phone lines on weekdays through early evening and for limited weekend hours. But after the operators ended their shifts, no one was available to answer transit questions.

That changed six years ago, when Eskenazi and SCS associate professor Alan Black launched the Let's Go system. Funded by the National Science Foundation, the project was designed to improve the response to spoken queries from elderly and non-native speakers, two groups that often have difficulty using voice-activated software.

Since going live in 2005, the system (trained to understand "yinz" and other idiosyncrasies of "Pittsburghese") answered more than 175,000 calls. It ran year-round under the watch of Eskenazi's team, filling in after-hours, when Port Authority's customer-service representatives weren't available. Coverage eventually expanded from eight transit lines to 60, representing more than half of the agency's routes, and 80 percent of the time, callers received the information they needed in an average of 1.5 minutes--success rates comparable to the best commercial systems.

"We have saved the Port Authority hundreds of thousands of dollars and provided a valuable service to the City of Pittsburgh," Eskenazi says. "It's nice to get out of the ivory tower and actually see people using what you are doing and be able to give back. And in the end, having applied research often pushes the research itself uphill."

More than 150 scientific papers reference Let's Go, and Eskenazi and her colleagues have amassed an invaluable real-world dataset to study spoken dialogue architectures and ways to improve speech interfaces.

And a new, highly robust version of their system--called Let's Go Now--was just launched using Tiramisu data to provide scheduling information for all of the county's bus lines. It operates 24 hours per day through a direct phone line (412-268-3526) independent of the Port Authority.

"It's a system that is going to be of much more help to the callers," Eskenazi says. "In many cases, they will be getting crowd-sourcing and historical information that is better than what we were giving them before. And they will have an even higher success rate in getting what they need."

Howard Stern, formerly the city's chief information officer, worked closely with Eskenazi and other SCS scientists while overseeing technology initiatives for the city.

"Running the city's technology shop for me was more than just keeping the e-mail system running and fixing a printer when it broke," says Stern, who was recently named associate dean of academic administration at Pittsburgh's Carlow University. "It was imperative to be imaginative and push the limits of technology, and CMU helped us push those limits by working on applications to make city government more efficient."

For instance, CMU computer scientists have helped to create digital maps of crime activity and school guard routes in the city. They have advised government officials in making critical decisions about issues such as citywide wi-fi. They are helping to create robotic devices that could help detect leaks in pressurized water lines, developing smarter traffic lights to alleviate Downtown congestion, and much more.

"When you can't raise taxes, how do you raise efficiencies?" asks Doug Shields, who represented the neighborhoods near the CMU campus on Pittsburgh City Council from 2004 to 2012. "Increased efficiencies come from technology applications, and many of those are available from some of the most brilliant people in the world right on our doorstep."

One source of funding for some of these applications, including Tiramisu, has been the Traffic21 initiative, launched three years ago by Carnegie Mellon with support from the Hillman Foundation.

Pittsburgh philanthropist Henry Hillman has provided the university with $1.25 million for this endeavor to create "intelligent transportation systems" for the region, such as traffic signals that adapt to congestion patterns and automated sensors to diagnose bridge problems.

Many Traffic21 (as in 21st century) projects are being undertaken with community organizations such as the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust and the Allegheny Conference on Community Development.

Through investment in the development of "smart traffic" technologies, CMU is helping the region access state and federal funds to deploy these systems, according to Traffic21 director Richard Stafford, distinguished service professor of public policy in the Heinz College. He says marketable solutions could also create new commercial spin-offs and improve the local economy.

"By partnering with the community," Stafford says, "we have created a test-bed for pilots of our technologies and created the opportunity to then make our research and development more relevant."

Several SCS faculty have received Traffic21 seed money for their work, such as Robotics Institute research professor Stephen Smith, who is piloting a system to improve scheduling for the Port Authority's paratransit service. Likewise, Robotics Institute senior project scientist Christoph Mertz is developing technologies to save money on road maintenance for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) and other public works agencies. Among Mertz's projects is an automated system that would use vehicle-mounted cameras to generate a 3D surface map of the pavement and help spot potholes.

Thanks to the early success of Traffic21, Carnegie Mellon is on track to receive a $3.5 million grant to become a federal research center in smart transportation. There's also a proposal to create--in conjunction with the University of Pennsylvania's School of Engineering and Applied Science--a new Consortium for Technologies for Safe and Efficient Transportation. The consortium would develop transportation applications that could influence everything from vehicle and road safety to the analysis of traffic flow, as well as launch a workforce development program.

"We have the CMU world interested in problem-solving and the real world that has problems," Stafford says. "Not all our faculty are interested in these kind of problems, and not everyone with a problem is interested in CMU intervening. At Traffic21, we are looking for the intersection between both worlds--that's the space that's really important."

It's a lesson that Kanade learned the hard way when the RODAS team went live with its pothole detector system last winter; there was some pushback from public works officials concerned about the negative image of their department being projected by the public reckoning of the city's road problems.

Pittsburgh City Councilman Bill Peduto says local government needs to be more open to technological solutions such as RODAS. Peduto, whose East End council district includes the universities of Oakland, cites the example of CMU President Jared Cohon's offer two years ago after "Snowmaggedon"--when more than two feet of snow fell overnight in Pittsburgh, shutting down CMU and other campuses--to harness university resources to develop a state-of-the-art snow removal route system for the city.

That offer wasn't accepted, said Peduto, who has frequently been at odds with his council colleagues and the city administration. "There wasn't a willingness to break from the pen, paper and clipboard (methods) that our guys use now," said Peduto, who argues that governmental agencies sometimes suffer from a cultural mindset of "this is just the way things are done."

Researchers who are proposing technology solutions for local government agencies soon find out that a big part of their work involves communicating with elected officials, says Acha-Alvarez, who worked on the RODAS project. Some of her greatest rewards, she says, come from figuring out how to do that part of her job better.

"I am a computer engineer, but I am also very interested in public policy," she says. "From my soul as a technologist, I know that technologies are just a tool. We are the people responsible to show the rest of the community why these technologies are important for them. If I'm not doing a good job at that, then it's my problem.

Says Acha-Alvarez: "I am still trying to figure out how to knock on the door and convince people: 'This is for you. I don't need this, but it will be useful for you.'"

Jennifer Bails is a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer who covers science and technology. Visit her website at jenniferbails.com.

Image2:

Image3:

Image4:

Image5:

Image6:

For More Information:

Jason Togyer | 412-268-8721 | jt3y@cs.cmu.edu